Katia Verresen's new client had a big problem: He needed to find 3 to 4 extra hours in his day. This, of course, seemed like an impossible feat for an oversubscribed startup founder, but his ability to fundraise and recruit the best talent depended on it. By the time he met Verresen, executive coach to many such founders, he was drained, pessimistic, dreading every week before it started.

Even though tech culture champions sleeplessness, overtime and burnout, Verresen has seen how this mindset can lead to failure. To turn it around, her first order of business is to collect as much data on her clients as she can and funnel it into a plan with one goal: Maximizing energy. Physical energy, emotional energy, and mental energy. These are the components of successful execution that are too often overlooked.

But the proof is in the pudding. After adopting Verresen's recommendations, her exhausted client said he felt like he had 60% more energy during the day, had a more hopeful outlook, and — by getting more done in the morning — found the four hours he needed in the evening. "Most importantly, he remembered that this was his for the taking," Verresen says. "He found control over his life so he could enjoy it again, while also closing on the funding he needed and building out his executive team."

Her method has turned Verresen into one of the most sought after coaches in the business.

Maintaining and using energy wisely might seem like obvious advice, but it’s hardly ever heeded. “How many times a day do you hear people bragging about how little sleep they got? Saying that they will just power through the next two weeks?” It’s common parlance for the entrepreneurial set. But it's rarely indicative of progress, Verresen says.

Instead, she encourages her clients to visualize three types of energy as buckets that need to be filled:

- Physical Energy: The foundation of everything you do. It's the type of energy that's most easily influenced but most often neglected (i.e. “All I’ve had today is Diet Coke,” “I can totally function on three hours of sleep”).

- Emotional Energy: How you're feeling at any given moment — excited, anxious, hopeless, etc. It dictates more than half of your behavior and decision making.

- Mental Energy: The highest order of energy, only achievable when you have the physical and emotional stamina to be observant, perceptive, and focus.

When these three buckets build on each other, people have a chance to reach what Verresen calls their “performance-plus” state. Some might call it flow, or “the zone” — it's that fluid productivity that can exponentially increase what you’re capable of as a leader in much less time.

This is where Verresen comes in — to offer a formula for achieving performance-plus as often as possible.

“To me, coaching isn’t just about changing someone’s environment, or tweaking their behavior — I don’t think that really works,” she says. “You have to change their belief systems. When someone becomes a leader, their external identity changes. To succeed, their internal identity has to catch up.”

If it was true that people can't change, we wouldn't have some of the most amazing companies we have today.

To gather the data she needs to urge this shift, Verresen not only has her clients audit their behavior, she conducts one-on-one meetings with the people they work with most. She collects a 360-degree inventory of how they interact, how their energy fluctuates throughout the day and how this impacts the decisions they make.

Most people know the core components of physical energy: enough sleep, eating right, exercise. But the dropoff between the people who know these rules and those who follow them is massive. On top of this, there's a lot going on physically that people don't even realize.

“So much of what we feel is instinctual, and we don’t know how to identify it," Verresen says. "If you’re a founder or a manager and you really track your physical sensations, you’d realize that you probably spend most of your time in ‘fight or flight’ mode.”

Humans needed this high-adrenaline setting when we were still part of the food chain. Now it surfaces in board meetings, product releases, whenever a threat is “perceived” even if there isn’t one. “The thing about ‘fight or flight’ is that it burns through our energy without us even knowing it,” she says. This is why preserving physical energy where you can is crucial.

To get a sense of her clients’ physical reserves, Verresen asks them several basic questions: How alert do they feel generally? What are their sleeping patterns like? Do they find time to exercise? Do they often take breaks between meetings or do they stack them back-to-back? What is their level of engagement in meetings?

Then she goes granular. Using a spreadsheet, she has them plot how alert they feel versus how tired they feel on an hourly basis. She has them do this for a stretch of three days to a week — enough time to see a pattern emerge.

“When you track things this closely, it becomes a movie you can replay. And when we look at the movie together, we can identify blocks of time where they are clearly more alert on a regular basis, and times when they are not.”

This extends beyond “being a morning person,” Verresen says. It’s knowing what hours of the day you are capable of higher-level thought. When can you tackle the gnarliest problems? When are you able to invest energy in tasks that aren’t easy or don’t have known solutions?

Verresen is a big fan of a tactic called “calendar blocking,” and she encourages her clients to identify the chunks of time on their calendars when they have the most physical energy for work. She has them do the same for the hours where they have less energy so they can plug in easy or lower-intensity tasks at those times.

Engineering your calendar to follow your personal energy pattern gives your productivity a huge boost.

Verresen has worked with a number of clients who were sure they were late-night workers. They claim to get the most done between the hours of 7 p.m. and 3 a.m. But when she reviews their energy logs, it’s obvious that they're only evening workers because they spend their days in meetings or being interrupted. Their only chance to focus is in the evening. This doesn’t mean they’re doing their best work at that time. Many of them work late, miss out on sleep, and then can’t handle anything in the morning — even though they’d otherwise be morning people.

Sleep is not as negotiable as people want it to be, and bargaining with it is the number one mistake Verresen sees people make. “Anders Ericcson has a famous study showing that the world’s best violinists slept an average of 8.5 hours every day to stay on top. For truly top performers, 8 hours are recommended," she says. "I’ll meet people all the time who say they are just fine with 3 or 4 hours, but you always end up paying that back in what you’re able to accomplish.”

To compensate, Verresen advocates naps. And if those aren’t possible, taking 10 minute breaks every 90 minutes to 2 hours becomes a saving grace. It doesn’t have to be a long break. It could just be standing up and stretching your legs, or getting a glass of water — but it should involve looking away from your screen and paying attention to your breath.

This is so important that she recommends her clients set a timer on their phones to remind them to take a literal breather.

“People tend to know these things, but when they are in fight or flight mode, they tell themselves they don’t have time for it, that they can’t possibly afford a context switch. The the goal shouldn’t be to push through, it should be to relieve this tension.”

One of fight or flight’s dead giveaways is a rapid heart beat. But this is easy to shake. Deep breathing is one very basic but proven tactic to elevate yourself out of this state — you want to feel the breath in your belly. It also helps to count your breaths. And, fairly quickly, you’ll start to feel more in sync with yourself, Verresen says.

“Without physical energy, we can’t even talk about emotional or mental energy,” she says. “But still, it’s the most easily disregarded.” This is a giant mistake, because your physical energy isn’t just about you, it’s about everyone around you too.

“Your energy level shows up in meetings, in the little things like body language,” she says. “Maybe you appear less engaged. You get impatient or frustrated that much faster. And your employees notice. The smallest ticks that you don’t even register change how people perceive you, how in control you are, their relationship to you. You think no one could possibly notice, but when I talk to their colleagues, it comes out right away.”

If people want to try peer coaching, Verresen recommends partnering with a colleague and walking through each other’s days to match alertness with high and low levels of efficiency. The important thing is to never edit anything out. Only then will you realize where you lost opportunities because you were tired, she says.

For Verresen, EQ has taken on new meaning. The assumed definition is social savvy, but it’s really a strategic approach to managing emotions that makes the biggest difference.

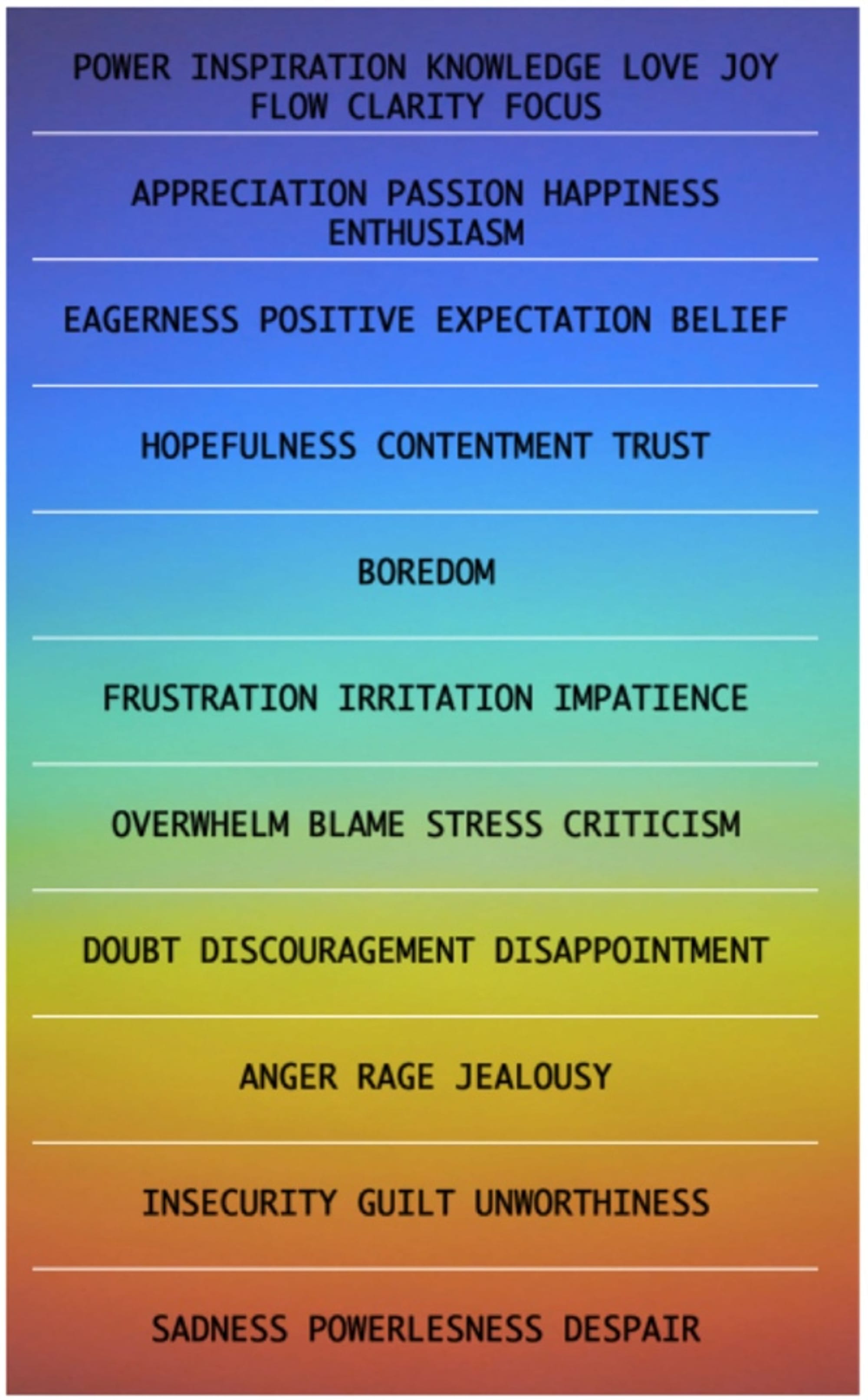

With the same chart they use to track physical sensations, Verresen also asks her clients to gauge their feelings throughout the day. To help, she gives them a chart codifying the spectrum of human emotions. At the top of the chart, you’re operating with performance-plus speed and agility. At the bottom, you not only feel demotivated, but helpless.

The goal is not for clients to always feel good about themselves and their work. Everyone is going to have low moments. Entrepreneurship is one big roller coaster. Rather, the objective is to give clients the tools and language they need to slingshot themselves from the bottom of this chart to the top when they need to.

“The first thing you need to do to fill that emotional energy bucket is become more self-aware,” Verresen says. “You already have a time set on your phone to take physical breaks. Take that time to really check in with yourself — what are you feeling at that moment? Taking your emotional pulse gives you a sense of how much juice you have left to get things done.”

If physical energy is your car, emotional energy is how much gas you have in the tank.

“All the time I hear people say, ‘I just need to get through the next two weeks, or the next month, or whatever. It sounds horrible but it’s become the norm,” she says. “The question is, then what? Do you really think you’re going to feel that much different? When we really start to look at our emotions, they become more predictable than you would ever imagine.”

When you have the data showing you always feel demotivated or anxious between 3 and 5 p.m. in the afternoon, you have the power to choose something different. “When my clients finally see their palette of emotions, I always tell them, now you can play with it.”

Making these changes starts first thing in the morning.

“The mood you wake up in is critical. Consider it to be the default font for your entire day. Think about it — when you wake up in a bad mood, it usually turns out to be a bad day. But if you’re aware of this, you can push the refresh button.”

This is also the time of day when the link between physical and emotional energy is most apparent. “When you’re physically tired, your buffer to regroup from stress or to shift out of a mood is vastly diminished. You’re basically unable to be emotionally resilient.”

This has proven to be so true that Verresen actually tells her clients that if they haven’t gotten enough sleep, they shouldn’t take their emotions seriously the next day. They won’t be indicative of what’s actually happening. And when you’re really tired, it’s probably a good day to disengage, work from home, cancel meetings, focus on easier tasks if you can.

Another big part of changing your emotions is understanding their triggers. Once a client has charted their emotions for several days, Verresen asks them the following questions: Before their most positive and negative emotions set in, who were they with? What were they doing? Especially if they were feeling good and their mood suddenly dropped, what changed?

If you know your triggers, you can decide whether to respond to them or not.

“Whenever someone tells me a meeting was challenging, instead of asking why I’ll ask what happened right beforehand. Usually that’s where the real answer is. Maybe they saw some discouraging data, or had a rough call."

The trick to busting triggers in these situations is to capture emotions and leave them behind. “People go from meeting to meeting without thinking that one influences their performance or responses in another,” Verresen says. “As a people, we give ourselves zero transition time, and the result is emotional transference.”

To prevent this spillover, you have to be very intentional about leaving baggage behind. “I tell my clients to imagine they are carrying suitcases and setting them down. This isn’t easy. It takes commitment and practice."

One especially counterproductive emotion Verresen sees is “comparison.” When it comes to high performers, it can be deeply destructive. “People think they are motivating themselves by comparing their level of success to others, but the underlying feeling is insecurity, powerlessness to change. It’s the easiest way to sacrifice all of your emotional energy.”

Comparison leads to anger and disappointment. This is bad enough, because it blinds you to other possibilities and stalls productivity. But on the outside — to colleagues and direct reports — it shows up as impatience, which can be even more toxic.

“This is a really big one with founders and leaders in tech because they naturally do things so fast, and they expect the same from everyone around them,” Verresen says. “They confuse impatience with efficiency. They feel like they are pushing things forward, but really they’re just spreading their anxiety.”

To flip this script, Verresen asks her clients to remember a time when things were operating efficiently. How did they feel when everything was running smoothly? Every time, they will say that they were feeling good — not anxious, not overworked, excited about the future. When you’re impatiently shoving things along, you don’t have any of these feelings.

Luckily, just like you can trick your heart into slowing down, you can trick your brain into thinking more positively by accessing memories. When you dwell for several minutes in the memory of something you were proud of, something you built, something that worked well, you will feel a psychological shift. And if you’re too upset to think about work at all, the same thing can be accomplished by thinking about something you really appreciate. It might be your family, or your dog, or beating Uncharted 3. It could be a time you felt safe or that you truly belonged.

When you take the time to recall these memories in elaborate detail, your brain lets go of the present and chemically changes.

“As an example, some of my clients are big into skiing and get into the zone on the mountain,” Verresen says. “So, when they get frustrated and need extra emotional energy, I tell them to visualize what it’s like to sail effortlessly down the slope. Same thing when they notice a trigger that could lead down the emotional spectrum, they can choose to front-load their brains with positive thoughts.”

Again, this may sound straightforward, but evolution isn’t on our side, she says. Because we were on the food chain for so long, humanity is biased to be negative and paranoid. “This is why it’s so easy for us to forget the moments when we felt good. You see it all the time in performance reviews. People don’t even hear the good stuff, they obsess over their areas for growth. Even if they just hit a big goal, they're already focused on the next problem.”

We delete our wins so easily. No wonder we don't see possibilities for the future.

Celebrating and revisiting recent achievements is the best way to re-wire your brain for clarity, Verresen says. This is especially important for CEOs and founders because it’s their responsibility to set the tone for everyone else — at all-hands meetings, in one-on-ones, with their board. “You need to not only recall wins for yourself, but to make everyone else really feel and savor them so they can draw emotional energy from them too.”

True clarity comes with mental energy. And while it’s not possible unless your physical and emotional buckets are already full, it can make the difference between being a good leader and an iconic leader.

“Mental energy is the ability to separate yourself from your thoughts,” Verresen says. “Everyday, we have millions of thoughts that cause stress, anxiety, depression — that can stall you out in a million different ways — but you don’t have to believe them.”

The Transformative Power of Mental Energy

Entrepreneurs are a worrying lot. They worry that things are taking longer than they should, that they aren’t hiring the right people, that they won’t close that next round of funding. The one things these thoughts all have in common is that none of them have played out. All they do is distort reality until, suddenly, you’re paralyzed.

Another quality entrepreneurs share: they often get away without paying full attention or investing their brainpower. Most of them have always been able to do this, since primary school all the way up through college. They’ve put in minimal mental energy but still succeeded, Verresen says. But when you’re building a company, you can’t just skate by.

“Mental energy allows you to have a much fuller view of what’s actually happening within your company and on your team,” she says. “When you have a lot of mental energy, your mind is like a video camera, picking up everything in every room and every situation. It also lets you observe without jumping to conclusions or making assumptions.”

True mental agility gives you the ability to read people without projecting anything onto them. Verresen recommends practicing this by noticing and taking responsibility for your projections when they happen. For example, if you’re feeling down about some data, and you notice yourself blaming a colleague for failing to make more progress — are you really criticizing your own performance? Call yourself out.

When you become familiar with the thoughts that take you out of your flow, you can see them coming and respond differently for a more powerful outcome. In meditation, people are instructed to notice when their minds stray from the present moment and gently guide them back. Similarly, Verresen advises clients to recognize destructive thinking patterns and steer themselves back to the task at hand.

“You hold onto your mental energy by observing yourself inwardly without buying into everything,” she says. “This is the part of your brain that notices what is going on and asks, ‘Are these thoughts I’m having even true?’”

There are several indicators that you're running low on mental energy:

- You find yourself mired in assumptions about things largely out of your control. Why did someone quit? How are things eventually going to fall apart? Is it all your fault?

- You can’t focus on a single task for more than a few minutes. You’re clicking off to Gchat or Facebook or anything other than what you need to get done.

- You look at the next task on your list and you already feeling overwhelmed.

- You're only reactive — all your work is short-term with no connection to long-term vision.

A lot of this has to do with feeling trapped — trapped in your head, in the moment, in a bad situation.

“The best way to reset your mental energy is to get it up and out into the physical world,” Verresen says. “Screens don’t count. You should put whatever it is that’s bothering you or that you need to get done up on a white board. Write it down and stick it up on a wall. Put some space around it. We all spend hours in our heads, staring into these little boxes. We need space to think.”

Giving something space also means giving it time. Verresen advises her clients to block off two slots ranging between 90 minutes to 2 hours every week as mental white space. They need to literally put it on their calendar and make sure they aren’t interrupted or disturbed during this time — ideally they shouldn’t have meetings right afterwards either.

“This time needs to be untouchable and scheduled during a period when you’re at your most alert,” she says. “The goal is to zoom out and to think through what’s going on at the present moment, and what you’d like to do in the future. This is where creative solutions and good ideas come from.”

This time should also be spent wherever they feel most comfortable and safe. Verresen personally recommends getting away from where you usually work, just to shift your perspective and limit chance of distraction.

When people have space, they are amplified. When they feel cramped, their abilities contract.

If possible, Verresen also recommends that her clients structure times when people definitely can interrupt and interact with them. Scheduled one-on-ones are an obvious need, but office hours have also proven to be effective at limiting interruption and distraction across the board. Especially when a company enters the growth phase and new people join, this can become a lifesaver. It maintains the image of having an open-door policy without the time suck.

“A lot of leaders feel like they are doing a good job as long as they're responsive or helping a bunch of other people with their needs,” Verresen says. “If they spend most of their time doing this, it usually means they're ignoring bigger, more important priorities.”

Putting it All Together

Fundraising is one of the most stressful experiences tech founders endure. It puts a tax on all three buckets of energy. There’s the lack of sleep. There are the ups and downs of pitches being rejected, accepted, torn apart. There's the non-stop interaction as they book meeting after meeting while still running their companies day-to-day.

Putting it All Together

“It becomes vital for you to manage your triggers,” Verresen says. “Investors express mixed emotions in every meeting, and when you leave you might feel terrible about yourself and your company. You have to be able to ask yourself, ‘Whose emotions are these?’ and put a boundary between yourself and the people you interact with."

Simultaneously, it becomes more important than ever to stock your mind with positive emotional reserves. “You have to constantly think back on what you've built, what you’re proud of, and the people you work with who you admire,” she says. “If you're in this business, you believe fiercely in what you're doing, so you have to ground yourself in that certainty that the money will come sooner or later. You shouldn’t buy into the worry or anxiety before it happens.”

Valuing yourself and your team becomes your number one defense against bottoming out. Just like you’d put on your own oxygen mask before assisting someone else on a plane, you need to take care of yourself first. Make sure you’re getting enough sleep, double up on your emotional check-ins, crack down on thoughts that aren't absolutely true. For momentum, focus on what’s working to counter-balance the natural negative bias.

“Fundraising is a marathon, but most people treat it like it’s a sprint and deplete all their resources right away,” Verresen says. “You can’t afford this. You need the mental energy to check your ego at the door, to realize that your negative feelings are normal but not predictive of the outcome.”

More importantly, you need mental energy to be thoughtful about the fundraising process. If you’re desperate to close a round just for the security, you won’t consider why you want to work with specific investors.

“You want to come out of a fundraising round with a group of strategic thought partners, not just the money,” Verresen reminds her clients. “You need to have the clarity to think about what needs to happen after the money hits your account. That’s what will determine your success in the long run.”

If you’re not careful, you end up going into pitches low on the emotional spectrum. That’s when prospective investors start looking a lot like the enemy. “If you make these people your enemy, you could miss out on a range of opportunities,” Verresen says. “You miss all the things working in your favor. You might not get the funding you wanted, but if you're observant and present yourself well, you could get it later — or you could get an invaluable mentor or advisor.”

Once the money is in the bank, it’s mandatory that you acknowledge the magnitude of the achievement.

“So often the depth of the stress and panic over fundraising drowns out the relief you feel once it’s over. You have to celebrate that win as thoroughly as possible. It’ll become one more tool in your belt when you need to give yourself vital boost in the future.”

Intel CEO Andy Grove contended that Only the Paranoid Survive. But Verresen disagrees. It's the people who have the mental fortitude to be fearless who survive and enjoy the ride.